-40%

1749 Gentleman's Magazine - Malta Slave Revolt - Santa Fe, New Mexico Revolt

$ 7.91

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

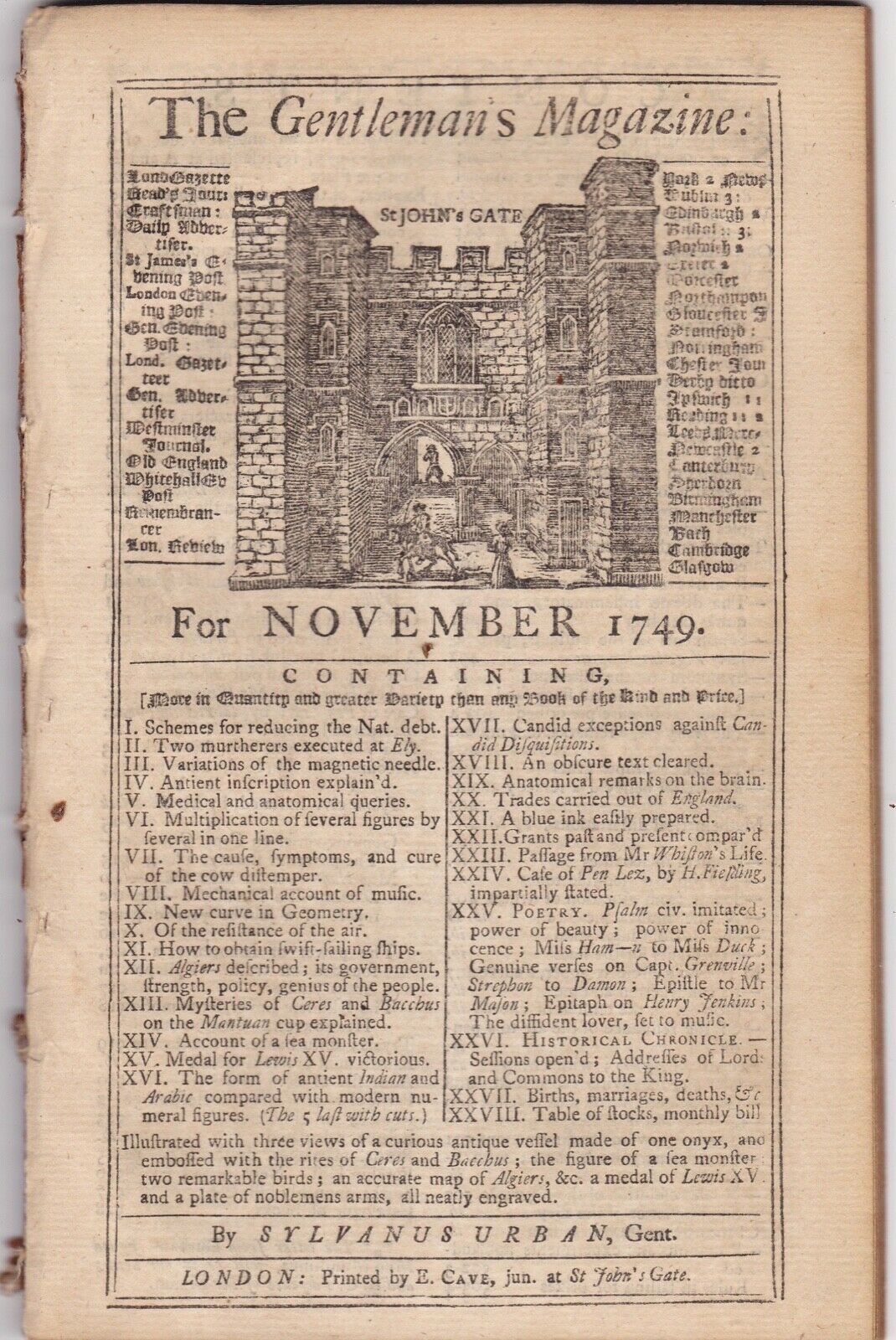

A rare and early monthly issue of the Gentleman's Magazine published in London for November 1749This venerable publication, the first to use the term "magazine", was founded in 1731 and continued uninterrupted for almost 200 years - see below. The magazine is full of domestic reports, essays, editorials, foreign news, poetry, new books, weather, births and deaths etc.

This edition of 45 pages reports two instances of revolt - one in Santa Fe, New Mexico where they have "appointed officers of their own body" - see scan - and in Malta where a

plan by the slaves to poison the knights was revealed - see scan and below

In other news the magazine provides highlights of the current state of Europe including Sweden, Germany, Spain, Italy, and France

Details on London deaths in the previous month by age group show children under the age of 2 representing approx. 30 % of the total - see scan. Giving birth at that time was a risky business.

Fascinating reading for the historian. G

ood condition. The magazine has been bound with other issues and subsequently dis-bound. Page size 8 x 5 inches

Note: The magazine cover calls for an engraving which has been removed and a "plate of noblemen's arms" which was not bound in until the supplement was published at the end of the year

See more of these in Seller's Other Items, priced at a fraction of most

dealer prices

The Gentleman's Magazine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Front page of

The Gentleman's Magazine

, May 1759

The Gentleman's Magazine

was a monthly magazine

[1]

founded in

London

, England, by

Edward Cave

in January 1731.

[2]

It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term

magazine

(from the

French

magazine

, meaning "storehouse") for a

periodical

.

[3]

Samuel Johnson

's first regular employment as a writer was with

The Gentleman's Magazine

.

Contents

1

History

2

Series

3

Indexes

4

See also

4.1

Authors of works appearing in

The Gentleman's Magazine

5

Artists, painters, topographers associated with

The Gentleman's Magazine

6

References

7

Further reading

8

See also

9

External links

History

[

edit

]

The original complete title was

The Gentleman's Magazine: or, Trader's monthly intelligencer

. Cave's innovation was to create a monthly digest of news and commentary on any topic the educated public might be interested in, from commodity prices to

Latin poetry

. It carried original content from a stable of regular contributors, as well as extensive quotations and extracts from other periodicals and books. Cave, who edited

The Gentleman's Magazine

under the

pen name

"Sylvanus Urban", was the first to use the term

magazine

(meaning "storehouse") for a periodical. Contributions to the magazine frequently took the form of letters, addressed to "Mr. Urban". The iconic illustration of

St. John's Gate

on the front of each issue (occasionally updated over the years) depicted Cave's home, in effect, the magazine's "office".

Before the founding of

The Gentleman's Magazine

, there were specialized journals, but no such wide-ranging publications (although there had been attempts, such as

The Gentleman's Journal

, which was edited by

Peter Motteux

and ran from 1692 to 1694).

Samuel Johnson

's first regular employment as a writer was with

The Gentleman's Magazine

. During a time when parliamentary reporting was banned, Johnson regularly contributed parliamentary reports as "Debates of the Senate of Magna Lilliputia". Though they reflected the positions of the participants, the words of the debates were mostly Johnson's own. The name "

Columbia

", a poetic name for America coined by Johnson, first appears in a 1738 weekly publication of the debates of the British Parliament in the magazine.

[4]

[5]

A skilled businessman, Edward Cave developed an extensive distribution system for

The Gentleman's Magazine

. It was read throughout the English-speaking world and continued to flourish through the 18th century and much of the 19th century under a series of different editors and publishers. It went into decline towards the end of the 19th century and finally ceased general publication in September 1907. However, issues consisting of four pages each were printed in very small editions between late 1907 and 1922 in order to keep the title formally "in print".

Series

[

edit

]

Top half of Volume One, Issue One, published January 1731

1731–1735

The Gentleman's Magazine

or

Monthly Intelligencer

1736–1833

The Gentleman's Magazine

and Historical Chronicle

1834–1856 (June) New Series:

The Gentleman's Magazine

1856 (July)–1868 (May) New Series:

The Gentleman's Magazine

and Historical Review

1868 (June)–1922 Entirely New Series:

The Gentleman's Magazine

1749 Muslim slave revolt in Malta

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

For the 1985

Voltron

episode, see

Revolt of the Slaves (Voltron)

.

Conspiracy of the Slaves

The revolt was to begin at the

Grandmaster's Palace

in Valletta

Native name

Konfoffa tal-ilsiera

Date

29 June 1749

Location

Valletta

,

Malta

Also known as

Revolt of the Slaves

Type

Attempted

slave rebellion

Organised by

Mustafa, Pasha of Rhodes

Outcome

Revolt suppressed

Charges

Most rebels executed

Part of

a series

on

Slavery

show

Contemporary

show

Historical

show

By country or region

show

Religion

show

Opposition and resistance

show

Related

v

t

e

The

1749 Muslim slave revolt in Malta

(known as the

Conspiracy of the Slaves

(

Maltese

:

il-konġura tal-ilsiera

) or the

Revolt of the Slaves

), was a failed plot by Muslim slaves in

Hospitaller

-ruled

Malta

to

rebel

, assassinate Grand Master

Manuel Pinto da Fonseca

and take over the island. The revolt was to have taken place on 29 June 1749, but plans were leaked to the Order before it began; the plotters were arrested and most were later executed.

[1]

Contents

1

Background

2

Plot

3

Discovery and aftermath

4

Consequences

5

In literature

6

See also

7

References

8

Further reading

Background

[

edit

]

Statue of a "captive

Turk

" in the

Maltese Church, Vienna

.

In the mid-18th century, there were around 9000

Muslim

slaves in Hospitaller-ruled Malta.

[2]

They were given freedom of religion, being allowed to gather for prayers.

[3]

Although there were laws preventing them from interacting with the

Maltese people

, these were not regularly enforced. Some slaves also worked as merchants, and at times were allowed to sell their wares in the streets and squares of

Valletta

.

[4]

In February 1748, Hungarian, Georgian and Maltese slaves on board the Ottoman ship

Lupa

revolted, taking over 150 Ottomans prisoner, including Mustafa, the Pasha (i.e.

Lord

or

Governor

) of

Rhodes

. They sailed the captured ship to Malta, and the prisoners were enslaved. However, Mustafa was placed under house arrest on the insistence of France due to the

Franco-Ottoman alliance

, and was eventually freed. He converted to Christianity and married a Maltese woman, so he was allowed to remain in Malta.

[5]

Plot

[

edit

]

Manuel Pinto da Fonseca

Mustafa planned to organize a slave revolt on 29 June 1749. The day was the

feast of Saints Peter and Paul

(

Maltese

:

L-Imnarja

), and a banquet was to be celebrated at the

Grandmaster's Palace

in Valletta. Slaves were to poison the food at the banquet as well as within the

auberges

and other palaces.

[6]

After the banquet, a small group of slaves would assassinate Grand Master

Manuel Pinto da Fonseca

in his sleep, while 100 palace slaves would overpower the guards. They would then attack the

Slaves' Prison

to free the remaining Muslims, while others were to attack

Fort Saint Elmo

and take weapons from the armouries. The

Ottoman

Beys

of

Tunis

,

Tripoli

and

Algiers

were to send a fleet which was to invade Malta upon receiving a signal from the rebels.

[7]

Discovery and aftermath

[

edit

]

The plot was discovered on 6 June, three weeks before it was to take place.

[8]

Three slaves had met in a coffee shop in Strada della Fontana (now St Christopher Street), Valletta, near the Slave Prison, to win the support of a Maltese guard to the Grand Master, and began to quarrel. The shop owner, a neophyte called Giuseppe Cohen, overheard them mention the revolt and reported this information to the Grand Master. The three slaves were arrested, and they revealed details of the plan after being tortured.

[7]

The leaders were subsequently arrested, and 38 of them were tried and executed. Some plotters reportedly converted and asked to be baptized just before being killed. 125 others were hanged in Palace Square in Valletta,

[6]

while 8 were

branded

with the letter

R

(for

ribelli

, 'rebels') on their forehead, and were

condemned to the galleys

for life.

[7]

On the insistence of France, Mustafa Pasha, who was behind the revolt, was not executed but was taken back to Rhodes on a French vessel.

[5]

Consequences

[

edit

]

The house in Valletta which was given to Giuseppe Cohen as a reward for revealing the plot. Since 1773, the building has housed the

Monte di Pietà

.

Following the foiling of the plot, Grand Master Pinto reported the events to his ambassadors in Europe. Laws restricting the movement of slaves were made stricter. They could not go outside the city limits, and were not to approach any fortifications. They were not allowed to gather anywhere except from their mosque, and were to sleep only in the

Slaves' Prison

. Moreover, they could not carry any weapons or keys of government buildings.

[7]

Giuseppe Cohen, who had revealed the plan, was given an annual pension of 300

scudi

from the Order's treasury and another 200 scudi from the Università of Valletta.

[7]

Cohen was also given a house in Valletta, which had previously been the seat of the Università until it moved to

new premises

in 1721. The house remained in the Cohen family until 1773, when they were given an

annuity

and the building was taken over to house the

Monte di Pietà

.

[9]

In literature

[

edit

]

The poem

Fuqek Nitħaddet Malta

("I am talking about you, Malta"), an early example of

Maltese literature

, was written by an anonymous author some years after the attempted revolt.

[10]

In 1751,

Giovanni Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis

published

Mustafà Bassà di Rodi schiavo in Malta, o sia la di lui congiura all'occupazione di Malta descritta da Michele Acciard

about the conspiracy. He published it under the

pseudonym

Michele Acciard, an Italian who de Soldanis had met in his travels (although some documents suggest that Acciard was actually involved in its writing as well).

[11]

The book caused considerable controversy since it attacked the Order and argued for the rights of the Maltese. This resulted in it being banned in Malta, and de Soldanis had to go to

Rome

to defend himself in front of

Pope Benedict XIV

. He returned in 1752 and was forgiven by Pinto.

[12]

In 1779,

Pietro Andolfati

wrote a play about the revolt, entitled

La congiura di Mustafa Bassa di Rodi contro i cavalieri Maltesi: ovvero le glorie di Malta

(The conspiracy of Mustapha Pasha of Rhodes against the knights of Malta, or the glories of Malta).

[13]

show